This winter has been brutally cold across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, grounding boats, freezing ramps, and curtailing any open-water fishing opportunities. But, the prolonged cold and snow may matter to anglers for a much bigger reason: striped bass have gone years without a strong spawn in the Chesapeake Bay, and winter conditions can play a critical role in determining how many members of the next generation of striped bass survive.

Striped bass abundance along the Atlantic coast is closely tied to what happens each spring in the Chesapeake’s spawning rivers. When conditions align, especially river flow and temperature during the spawning and larval period, the Bay can produce year classes that support the fishery for a decade or more. When they don’t, the impacts show up years later as fewer schoolies, thinner age classes, and a less robust spawning stock. After a long stretch of weak recruitment, including the absence of a strong year class since 2019, even small improvements matter. Cold, snowy winters have historically helped set the stage for more favorable spring conditions in the Chesapeake, offering cautious optimism that this winter—however miserable it’s been for anglers—could improve the odds for striped bass at a critical moment for the stock.

For striped bass anglers, the stakes are simple: weak Chesapeake spawns over the past several years have left fewer young fish in the system, particularly the schoolie stripers that define spring and fall fishing for shore-based fishermen. With no strong year class since 2019, the conditions shaping this spring’s spawn could help determine whether striped bass abundance continues to slide or finally begins to stabilize.

Why the Chesapeake Bay Matters to Every Striper Angler

The Atlantic coastal migratory stock is largely driven by spawning in the Hudson River, Delaware Bay, and Chesapeake Bay system, with the Chesapeake Bay the most important significant contributor. Whether you fish New Jersey in April, Cape Cod in June, or Montauk in October, the health of your striped bass fishery is closely tied to what happens hundreds of miles south in the Chesapeake Bay, the single most important spawning and nursery area for Atlantic striped bass.

A large majority of mature Atlantic striped bass migrate into Chesapeake tributaries to spawn, which the Maryland DNR describes as America’s largest striped bass nursery. That matters because striped bass don’t show up overnight. A strong spawn in the Chesapeake today becomes schoolie stripers three to five years down the road, and eventually the spawning stock that sustains the fishery. When Chesapeake recruitment falters, anglers feel it years later. If you’ve noticed fewer small stripers, you’re almost certainly feeling the results of poor recruitment and smaller year-classes from the Chesapeake.

A Long Stretch of Weak Spawns

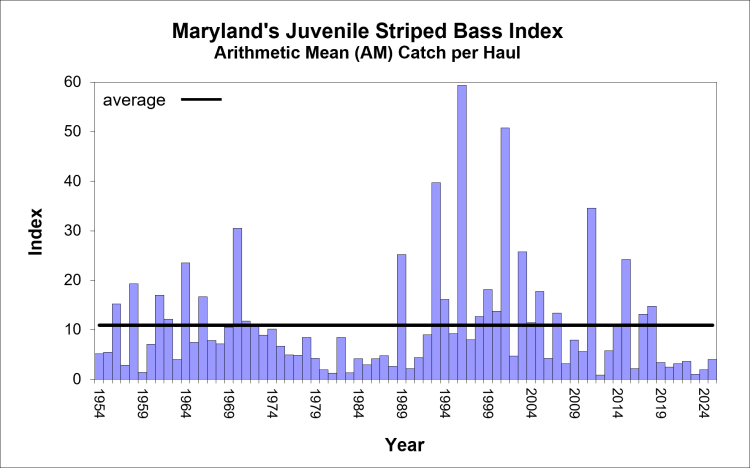

Maryland’s long-running juvenile striped bass survey, the benchmark for Chesapeake recruitment, has documented persistent poor spawning success. While there have been occasional modest improvements, there has not been a strong year class since 2019, and several recent spawns have ranked well below the long-term average. This prolonged recruitment slump is a major reason the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) reported striped bass as overfished in its most recent stock assessment update and implemented tighter regulations, including a coastal slot limit, while considering seasonal closures.

How Winter Weather Actually Influences Striped Bass Recruitment

Cold weather alone doesn’t “save” striped bass, but winter conditions can influence the factors that matter most during spawning and early survival. Decades of Chesapeake Bay research point to one consistent finding: spring freshwater flow is one of the strongest predictors of striped bass recruitment.

Peer-reviewed studies have linked stronger year classes to higher March–April river flow, particularly from the Susquehanna, because flow can shape salinity gradients, larval retention and transport, and the distribution and availability of plankton prey in nursery areas (North & Houde, 2001; Martino & Houde, 2010). A more recent synthesis evaluating the “poor recruitment paradigm” across tributaries also supports the central role of freshwater discharge in recruitment outcomes (Gross et al., 2022).

Cold, snowy winters matter because they can lead to stronger spring runoff. When snowpack melts during the spawning window, it can produce the kind of flow conditions historically linked to better survival. Maryland DNR has pointed to this connection directly, noting that the exceptionally strong 2011 year class followed a cool winter and wet spring, while the record-low 2012 spawn coincided with warm conditions and low river flow (Maryland DNR, “Warm winters, low water flow are leading factors in poor striped bass spawn,” 2023).

Striped bass larvae survive—or don’t—based largely on timing. They must hatch when the right plankton prey is available in sufficient numbers. Research published in the ICES Journal of Marine Science suggests winter water temperature can influence the development timing of copepod prey, affecting whether larval stripers overlap with adequate food during their brief survival window (Millette et al., 2020). In simple terms, winter conditions can help “set the clock” for the spring ecosystem.

Cooler winters may improve that match in some years, but it’s not automatic, and it interacts with flow, habitat quality, and broader ecosystem change. Higher flow and cooler conditions increase the odds, but they don’t override everything else. Habitat loss, predators (including the explosive increase in the invasive blue catfish population), water quality, and long-term climate trends all play a role. Some high-flow years still produce weak spawns, and some average years surprise scientists.

Why This Winter Has People Paying Attention

This winter has been persistently cold across much of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. Snowpack, frozen ground, and extended cold snaps raise the possibility of elevated spring runoff, especially if temperatures warm gradually rather than all at once. That’s why biologists will be watching Chesapeake conditions closely in March and April. River flow, water temperature, and plankton development during that window will give them a more complete picture of the likelihood of striper spawning success. For a stock that has endured years of poor recruitment, even a setup that looks promising is worth noting.

One good Chesapeake year class wouldn’t fix striped bass overnight. It wouldn’t immediately loosen regulations or flood the coast with fish. But, it would matter immensely. A strong spawn would rebuild the schoolie pipeline, strengthen future spawning stock, and give managers more flexibility and options as they rebuild the striper stock.

Great reading, the cold has been brutal, but the payoff could be a good thing for us fishermen.

Great article Kevin, growing up on the south shore as a young buck we always loved a snowy winter as we knew it meant a healthy striper run with plenty of bait! Tight lines.