The autumn striped bass run comes on like an insatiable mistress, demanding all an angler’s time and money, putting a strain on his marriage, derailing domestic obligations, alienating the fisherman from the family. Saltwater temperatures keep falling and induce the now-or-never anxiety that makes you take up the rod one last time.

And then, quite suddenly, the season ends.

It ends at the moment when a fisherman is threading monofilament through the last guide at the rod tip and, by memory, ties the serial loops of an improved clinch knot. Whereas in summer he avoided the heat, now it is a pleasure to stand with the warmth of the sun on his back, and an added pleasure to be sheltered from the wind by a group of laurel bushes and cedar trees.

A diehard chicken-neck crabber stands frozen on the bank of Elder’s Creek, his arm extended over the salt creek, his box trap suspended at that precise instant when it is about to slap against the olive-green surface of the chill water, the four side panels of the cage already dropping as the taut draw lines holding them up go slack. The man is an optimist casting into water that is very likely too cool for crabs.

The clammer with his thighs braced against the gunwale of his Carolina skiff is lifting his long-handled clam rake, watching the water pearls piddle from it as the aureoles of their splashes spread on the surface of the bay water.

Cast from the bank of another mid-Atlantic saltwater creek, a flashing tin spoon is in mid-wobble on its way to the bottom, and a great, green, big-bellied cow of a striped bass is about to strike, its jaws opened expectantly behind the sparkling lure—but it does not take. Instead, the fish cruises inches above the dark mud bottom, following the abrupt mechanical jerk of the spoon as it rises and falls against the more languid undulations of the sea weeds, and then ignores it altogether.

A solitary back-bay fly-fisherman feels the undeniable desire to stop casting and observe the wash of autumn sunlight fanning over the expanse of salt marsh that has aged to a golden-green flecked with dying red flowers and browning vegetation. He looks out at the salt meadows, the distant reds and yellows of the grasses, the pale greens of the deciduous trees of the lowland woods marking the high ground, and he feels, oddly, as if the whole tableau is vanishing quietly and leaving him behind.

Focusing on the meadow closer to where he stands, concentrating on a cedar tree standing in the middle distance, the fisherman sees a single long-necked snowy egret landing, its wings spread to the failing sun in a posture of crucifixion. The tall brown feathery reeds along the banks remain bent slightly east by the west wind as though turning their backs to the sun.

There is a crispness in the air, as if autumn has been blown clean, and a chill makes the air seem emptier and all the fauna more distinct. The fisherman is forced to look overhead by the honking of migrating geese heading off before the coming cold in their chevron flight toward the Delaware River and parts south. The clouds are turning deep purple, surreal, and the landscape is reminiscent of early 18th century paintings that made the American wilderness look Edenic. Gradually, the fisherman realizes that everything is gone like drifting smoke, and he feels as if he is instead in a recollected dream of fishing.

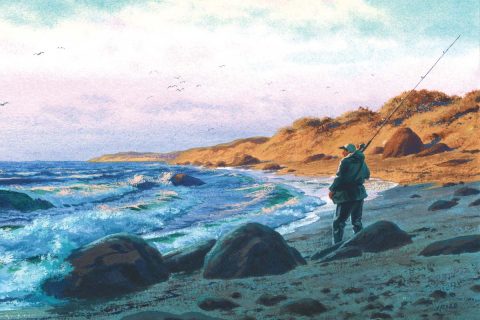

Surf fishermen feel the chill of the water penetrating the skin of their rubber boots and waders, the cold stiffening their wet fingers, a discomfort bordering on pain. The waves break at their knees. There are no birds working, no bathers bathing, and the red, white and blue lifeguard stands that marked the protected beaches during the summer months are all gone. The fishermen, more or less, have the beaches to themselves, and there are very few boats on the water. Most of the outboards have been fogged by now, the gas tanks winterized with Sta-bil, the bottoms steam-cleaned, and the cushions and life jackets stored in the shed. The surfcasters know that when they get back home, the first drink will likely be warming whiskey and not thirst-quenching beer.

Both the fisherman alone on the mudbanks and the clammer in his boat feel a creeping sense of longing for the fishing they will not do any more this year, mitigated by a sense of relief at not having to do it now. Watermen throughout the mid-Atlantic feel the kind of closure that a farmer might feel after the crop is in.

Anglers breathe out, relax. Later, the way the farmer tends to his idle equipment, the fisherman will tend to his salted gear. Facing the oncoming winter freeze, both farmer and fisherman look ahead to the spring thaw.

Now, it seems, there is a void to fill: all sorts of concerns want in. The immediate future is vacant and tomorrow a vacuum with respect to the sport. What will you do to fill the temporal emptiness that opens before you like an expanse of open water. If you’re not careful, you may find yourself thinking about joining a gym, jogging, or even golf.

Tomorrow, you will awaken with a certain reluctance, thinking there’s nothing to do but those odd jobs to which impending winter adds importance, draining the outdoor shower pipes, putting in storm windows, all the anticipatory chores that fall under the general heading of “battening down.” The soles of your bare feet will register the chill of the cool oak floor. Downstairs, the coffee will have a more welcome smell and a taste you want to linger over. To the northeast, the skies darken, and you will think not of rain, but of snow. You will wonder when the robins might return.

beautiful.

Anybody know what painting/artist that is? Beautiful painting!

1000 words are worth a picture. Well done. I felt all of this the past weekend.

Brothers, I cleaned my kayak and put it up on the garage wall, I sharpen all the hooks in my tacklebox, next week I’ll re-tie my line and leaders, so on that first warm day I am ready. Martin in Freeport

Beautiful and that painting looks like Southwest Point!

Wonderfully stated

Every November and sometimes early Dec. on a warm day I’ll go out knowing this formula. What may have been 20 fish in an hour weeks earlier is now with a lot of luck a fish for every 20 hours. Late season is like the lottery. If you like to play keep playing though you’re well aware of the odds !

Incredible language. This perfectly captures what so many of us are feeling right now. I am grateful to be only miles away from the Housatonic River… so without ice the chase can continue deep into winter.

Great shot of John Schillinger in the rocks….Man..