The winter flounder, aka blackback flounder, is a popular gamefish that ranges from Labrador to Georgia. On average, they grow to 18 inches in length and 2 to 3 pounds in weight. Blackbacks that inhabit deeper waters, such as those found at Georges Bank, have the potential to grow much larger, with some specimens measuring 24 inches in length and weighing more than 6 pounds.

The winter flounder is so-named because while all other local species of fish are heading for warmer waters during the fall/winter, it migrates into coastal estuaries to spawn. With water temperatures dropping below freezing, conditions can be brutal. To combat subzero temperatures, winter flounder blood contains an antifreeze protein that protects them in temperatures as low as 29 degrees Fahrenheit.

Spawning takes place when water temperatures are between 32 and 37 degrees. Like many other fish species, fertilization of the eggs takes place externally. As a female winter flounder swims in circles along the bottom, she will lay clusters of eggs that will then be fertilized by a following male. Unlike most fish eggs that are semi-buoyant, winter flounder eggs are negatively buoyant and will stick to the bottom, seaweed, or eelgrass. This ensures that the eggs will stay within the estuary where they will be protected and have an abundance of food upon hatching.

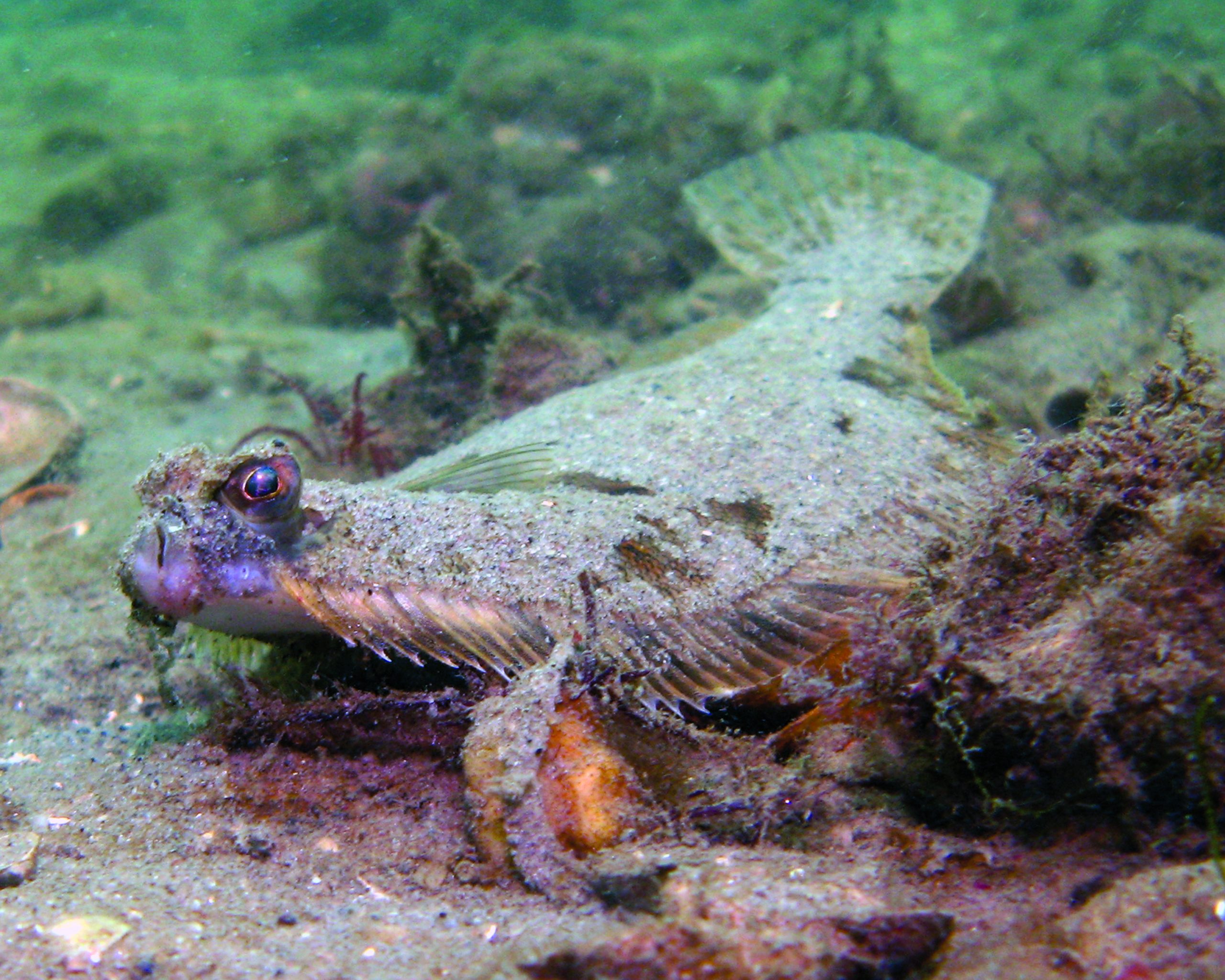

When it hatches, a larval flounder is like other fish – it has one eye on each side of its head and swims upright. As it develops, the larva goes through a transformation where one eye will migrate to the other side of the head, and the fish will begin to spend its time lying flat on the bottom.

The side where a flatfish’s eyes are located on varies among the different species of flounder, and this is one way scientists categorize them: right-eyed and left-eyed flounder. The winter flounder is a right-eyed flounder.

One of the most obvious differences between a winter flounder and a summer flounder is the mouth size. Since it has a small mouth with no visible teeth, the winter flounder is often thought to be a scavenger. Although it will scavenge the remains of clams, oysters, and mussels that were previously preyed upon by crabs, it is also an active predator. Feeding primarily by vision, it will raise its head up a few inches off the bottom to scan the surroundings for worms, amphipods, shrimp, fish eggs, and larval fish. If nothing appealing is spotted, it will move along to a new location. When something tasty does catch its interest, it will slowly undulate its dorsal and ventral fins to propel it along the bottom. Once in striking range, the fish lunges forward and slurps the prey up in the blink of an eye. This feeding behavior is why sinker bouncing and colorful grubs/beads are often used when anglers are targeting blackbacks.

The winter flounder fishery has been one of great importance for both commercial and recreational industries for decades. The commercial harvest had landings of 40.3 million pounds annually until the early 1980s, while the recreational sector peaked in 1982 with 16.4 million pounds. Catches in both sectors have been at all-time lows since the “glory” days prior to the 1980s and continue to decline, even with the implementation of short seasons and tight bag limits. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission currently lists winter flounder as overfished, but it is not currently occurring. Why, with strict regulations, has the winter flounder fishery not made a comeback like other fisheries?

I see an abundance of young-of-year winter flounder on just about all my dives throughout the bays of Long Island. I also see quite a few mature fish while doing research trawls in these same bays. One thing I do not see are juvenile winter flounder. What is happening to these fish? Insufficient habitat? Predator/prey imbalance? Climate change?

Researchers at Stony Brook University are currently looking for answers as to why the winter flounder fishery has not rebounded and I hope they succeed in their quest. For me, winter flounder are more than the first fish to target of the season. They have been responsible for my addiction to fish. If not for winter flounder, I most likely would not have pursed a career in marine biology and certainly would not be writing this column.

» WATCH: Fishing for Winter Flounder on Cape Cod

With a degree in marine biology from LIU/Southampton, Chris Paparo is the manager of Stony Brook University’s Marine Sciences Center. Additionally, he is a member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America and the NYS Outdoor Writers Association. You can follow Paparo on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter @fishguyphotos

May want to get the Cormorant population in check. I see them devour small flounder all the time during my putt putt down the river. Hundreds of birds in such a small area. Can only imagine the number of fish they take out collectively.