by Tim Coleman

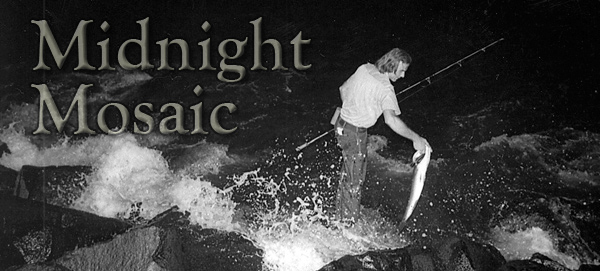

From May to October, the late night drive from Westerly, Rhode Island to the water’s edge at Galilee is usually uneventful. One might see a deer or a police cruiser, but traffic on the weekdays is usually light. That’s the point of the operation – light crowds on the short jetty at the start of the ebb tide. On the way, nursing the usual cup of black coffee, one has time to look back, to remember bits and pieces of 46 seasons, putting them together in order over a lifetime spent chasing striped bass.

Each story has a beginning and this one starts on the north side of First Avenue jetty in Asbury Park, New Jersey in 1964. After fishing the polluted carp rivers around my home town of Philadelphia, the manmade jetties of north Jersey were God’s country. That morning a clumsily cast 5 ½-inch Rebel with blue top and silver sides was followed back to the rocks by a “huge” bass of 22 inches. So struck at the sight of the fish behind the plug, I jerked the lure away from the fish.

Instead of bolting away like a smart fish, this one dove under the rocks, thinking its prey had hidden there. The next step was to toss the plug underhanded roughly five feet away and move it parallel to the jetty edge, where to my everlasting surprise, the bass sped from cover and grabbed the plug, not letting go. A striper fishing career was born.

For the next 10 or so years, the “Joisey” jetties and adjoining beaches were my home. There I learned, stumbled, laughed, learned some more, and always listened for the next tip to make my all-consuming avocation even more productive. Of course, not everything I saw on those jetties made me a better fisherman. One late night, taking a break in the fisherman’s lot at Eighth Avenue in Asbury, I saw a light turning on and off out on the jetty. Thinking somebody was catching something, I walked down to find one guy holding a light and a second guy casting out a surface plug. The first guy was shining the light on his buddy’s plug as it swam back toward the jetty – “so the bass would be able to see it on a dark night,” he explained.

Another time, in the wee hours of Monday morning, I was fishing the drop-off on the tip of Sandy Hook when a 30-foot cabin cruiser cut the channel marker on the wrong side and then, to my wide-eyed wonder, plowed right up on the deep-cut shore not 20 feet away. Out popped three “captains,” each one slightly more gassed to the gills. Two jumped out to help push the boat back into deeper water. Once they did, the third captain took off, leaving his buddies high and dry. I ended up giving them a ride to the Highlands Bridge, leaving them there to flag a cab for the hefty fare back to their homes in North Jersey. After thanking me for the lift, they let me know as I drove away that they had definite plans to reconnect with their third friend and “Kill that son of a …”

Any stay along a section of beach produces associations and friendships. I remember fishing with Steve Kalek in his VW van, taking some of the first pictures for my first-ever story on stripers that was accepted by the now-defunct Garcia Fishing Annual. Steve built a genuine log cabin home among the more traditional houses in Shark River Hills, but has since gone to Alaska to take up commercial fishing.

Billy McFaddden was a teacher in northern Jersey who quit his job and moved to Ocean Grove to be closer to the bass he loved. The late George Carlin (not the comedian) worked during the day in the local post office and by night taught me a lot about jetty jumping. Russ Wilson was then the circulation manager for the Asbury Park Press and a great striper catcher who went on to become one of the area’s most respected fishing writers.

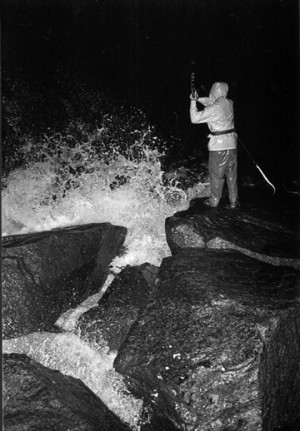

Among the many things these and others taught me during my first decade of striper chasing was that the beat-up, broken-down jetties were the least fished because the rocks made walking, even with spikes on the bottom of a pair of hip boots, difficult. Places like the first jetty north of the Ocean Grove pier at McLintock Avenue were good, as were two of my favorites, Hathaway Avenue in Deal and the famous Humpback, the latter built before World War II. Even in the 1970s, this jetty was so beat down it was only accessible by wading through knee- to waist-deep water at the very bottom of the tide. And even then you could only stay for an hour-and-a-half unless you wanted to swim back to shore.

The fishing was all done with 7- to 7 ½-foot rods; long casts weren’t needed as the fish we usually right at your feet, feeding close to the jetty rocks where the food was. Two of the favorite lures in the 70s were the rigged eel – a smaller eel rigged with metal squid in the head and tail hook in the back – and the 5 ½-inch Rebel or the new (at the time) Redfin. I consistently saw the latter plug catch bass into the 30-pound-range (when the hook hangers weren’t pulled out of the plug), but when I moved to Rhode Island the locals scorned at using something that little for bull bass.

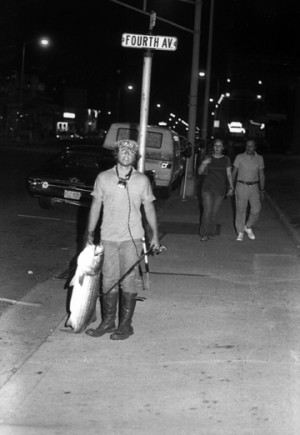

I, along with my compatriots at the time, was a little less than well-heeled, so any fish caught were carted off to a nearby fish market to be sold. The manager of one such market didn’t like 40-pounders much because they took up too much room in his display case. Whatever money we made got plowed back into fishing or a tank of gas to head home, or maybe a meal for the next night’s fishing.

If you stopped by the Eighth Avenue lot along the Asbury oceanfront, you’d see the crew assembled prior to nightfall, many eating grinders from the Allenhurst Sub Shop. A turkey grinder was the most expensive, tuna the least. A visual check of what everyone was eating would often provide clues as to how the fishing was the night prior.

If all hands had a good night, the scales at Young’s Esso gas station would be busy as people stopped by to B.S. and weigh-in their fish for either the Schaefer Contest or for possible prizes in the Asbury Park Club Contest.

Among the many aspects of striper fishing discussed at the lot was the seemingly endless supply of striped bass being caught up the road at a place called Rhode Island. Two of the steadies made yearly runs up I-95, returning with tales of more bass than I could believe, locals up there totaling four to eight times more bass per year than even the hardest-hitting Jersey jetty jockies, as the “rock hoppers” were called back then.

In time, the lure of Rhode Island became too much, so it was up the road for me, tipping my hat to friends, bound for what I hoped was the state where bass swam down the main street of every coastal town. I can remember infrequent appearances at dinner parties, telling my hosts I chose my college not because of a fraternity or curriculum, but because it was near great striper surf. After a pause of uncertain silence, maybe some nervous coughs, the conversation quickly shifted. Funny, I never seemed to get an invite back. I was obviously not a corporate climber.

If the Jersey jetties were good, all the God-given rocky shoreline around Point Judith and Narragansett was Nirvana. It looked like a bass could be hiding behind every rock. During the day, I took classes at URI, while at night I cast for striped bass from Deep Hole to Hazard Avenue. Sometimes I fell in, but occasionally I filled a plastic fish tote with bass and took them over to the Point Judith Co-Op early in the morning, making it to my class on “newspaper writing” right on time, smelling like success.

Not only did Rhode Island have natural rocks, it also had jetties, very much like those in New Jersey. Places like the Sheep Pen, East Wall and Short Wall were magnets for a striper hungry fisherman like me. The first time I ever set foot on the latter spot was a Fourth of July night in the 1970s. George’s Restaurant was rocking, but there wasn’t a soul on the jetty. I still have the old log from that night: five bass to 31 pounds on 1- to 3-ounce bucktails and pork rind. Roughly 35 years later, the bass still line up in the current in the same spots they did back then.

In Rhode Island, the fishing methods shifted from 7-foot jetty sticks with 5 ½-inch Redfins to 10- or 11-foot spinning or conventional rods tossing live eels or bigger plugs like the Atom Junior or Atom 40. Rigged eels were rigged with two hooks, not on a metal “squid” as in New Jersey.

While down south, I watched in the spring as people live-lined herring from the tips of all the jetties. I mentioned that it might be worth a try up in Little Rhody but was told that while herring were good in boats, they probably wouldn’t work from shore. The very first June morning I flipped a live buckeye (Rhode Island slang for river herring) into the pocket at the back of the East Wall, it swam maybe 15 feet before a 41-pounder nailed it cold.

During my Rhode Island “internship,” the late Ron Wojcik showed me how and where to fish Point Judith Light with an Atom Striper Swiper; later we used a hot new lure called the Danny swimmer. Further up the coast I met Captain Charley Soares. He and I cast Dannies around the Sakonnet Point rocks, then later in the day trolled with another hot new combo at that time, the tube and worm. I still have a photo of Charley in his back yard with a nice mess of bass to 49 pounds. I had found a home.

Steve Smith, a native Block Islander who’s since moved back to the mainland, took me around the island in the early 1980s, showing me spots and giving me tips that served me well – and I had nothing to offer in return except a thank you.

Much has been written about Block in the 1980s, much of it deserved, but some nights during the “good old days” were long and lonesome, and I struggled just to catch fish number one. One night in early December, George Thackeray and I dropped bass on the west side a little after 4:00 p.m., just before sunset. We fished all night without a single bump until 4:00 a.m., back where we started, we got our second hit, the only joy in a very, very, very long night up and down the cliffs of the island.

Please keep in mind we were fishing only spring and fall. We’d make a few trips in the spring from late May through June, then pick it back up from late September to early December. Most of us were working, so we were limited to once or twice per week, as much as we could spare from our jobs. Even then, people like Dr. Frank Bush often caught 40- or 50-pounders before heading back to our rented house for a few hours sleep before flying back to Rhode Island then driving off to his practice in Connecticut.

How good was the catching? Here’s a sample: On June 8, 1984 I landed 17 bass from 6 to 40 pounds at Southwest Point. The last entry in my old log was “all released alive.” Selling bass was over for me by then. That year, totaling up the whole season, I see I caught 11 in the 40s and three in the 50s.

Over on the mainland, the stripers were dwindling but blues were on the rise in both size and numbers. That same year, the log shows loads of big blues hitting the Dannies. I only counted the bluefish that were heavier than 15 pounds, and in the fall of 1984, I caught 19 over that size, along with a 13-pound weakfish on a 7-inch Redfin.

Over on the mainland, the stripers were dwindling but blues were on the rise in both size and numbers. That same year, the log shows loads of big blues hitting the Dannies. I only counted the bluefish that were heavier than 15 pounds, and in the fall of 1984, I caught 19 over that size, along with a 13-pound weakfish on a 7-inch Redfin.

At that point we were seeing the last of the remnants of the great 1970s weakfish run, and their numbers were down greatly, but the ones left were approaching 15 pounds.

Rhode Island still has plenty to offer the fisherman. It is a state where many beaches remain open for most, the rocks impervious to time and tide. It also offers a longer season than areas to the north, starting in the rivers in April, and some seasons lasting into December. A few years back we had a decent bluefish blitz at the “Blue Shutters” on December 4, and single blues could be caught after that at sunset for two more days until the water temperature dropped below 50 degrees.

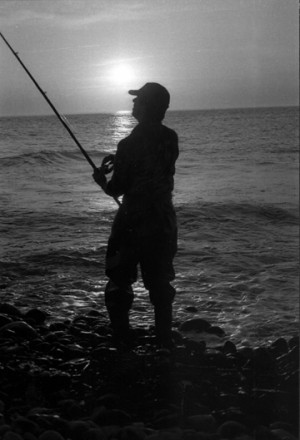

I hope you’ll excuse an older guy for blabbering on and on, which I usually do when the subject of bass comes up. It’s time, though, to get down to business. The turnoff for Point Judith is coming up in the headlights and I have to stop at the Mobil station on the corner, get rid of some coffee, and then see what the Short Wall has to offer.