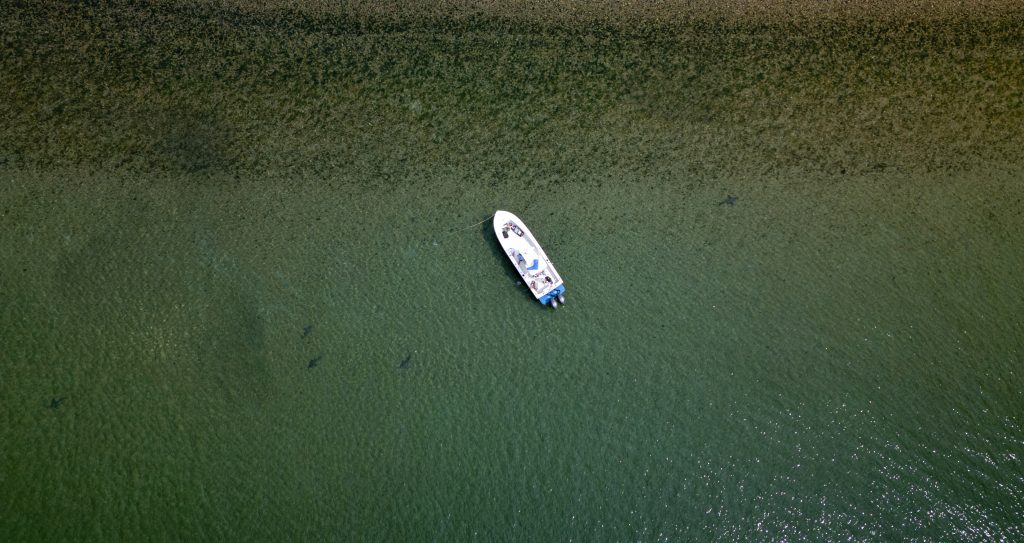

Water sprayed over the boat, soaking my clothes and some of the gear, but it wasn’t from a wave. The sandbar shark powerfully thrashed as I tried to wrangle it onto the boat for tagging and release. Alien abduction, it was probably thinking. And, honestly, it wouldn’t be wrong.

At least it probably resembled an alien abduction in many ways. The shark, lured by what seemed like an easy meal, was pulled toward a bright light, poked, measured, and examined by strange beings. Then, just as suddenly, it was released—free to return to its world, with only a strange tag as proof of the encounter.

As a PhD student working with UMass Boston and the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium, I’ve spent the past five years studying sandbar sharks in Massachusetts. While being caught and released may be disorienting for them, they are providing us with invaluable data. With each shark we catch and each tag we deploy, we learn more about their population, habitat use, migration patterns, and how environmental conditions may affect these.

Sandbar Sharks

The sandbar shark, also known as a brown shark, is a large coastal species that ranges from Massachusetts to Brazil. It can reach up to 7 feet long, but grows slowly and doesn’t reach sexual maturity until around 15 years of age. Its palate changes throughout life, beginning with smaller fish and crustaceans, and later broadening to include larger fish, like menhaden, bluefish, and fluke.

Juvenile sandbar sharks tend to inhabit inshore and estuarine areas, with major nursery grounds in the Chesapeake and Delaware bays, and along the southeastern U.S. coast. As sandbar sharks grow, they leave their nursery grounds and adopt a more mobile lifestyle, often engaging in seasonal migrations. In the summer, most travel north, reaching as far as Massachusetts waters before heading back south to the Carolinas (and sometimes beyond) for the winter.

In the 1980s and 90s, sandbar sharks were heavily overfished along the U.S. east coast, leading to an 80% population decline. Federal protection came in 2008, banning retention of the species in both commercial and recreational fisheries. Recovery has been slow, but over the last decade, signs of rebound have emerged. Growing up fishing and swimming along Nantucket’s shores, I’ve seen firsthand how our local shark population has changed around the island since the 90s. As a kid, I spent nearly all my free time by the ocean and remember rarely seeing sandbar sharks. We’d occasionally spot a sunfish at the surface but, nowadays, if you stroll along Great Point, you may see a friendly fin or eerie shadow in the water, or even a couple of them at once.

Over the past several years, I’ve also observed a noticeable increase in the number of recreational fishermen targeting sandbar sharks along Nantucket’s shorelines. Massachusetts state law allows fishing for sandbar sharks recreationally, but captured sharks must be released.

Despite their increasing presence, research on sandbar sharks in Massachusetts has been limited. Dr. Greg Skomal’s work from 1989 to 2002 documented juvenile sharks around Martha’s Vineyard and, more recently, I assisted in my advisor’s work on post-release survival of sandbar sharks in the local recreational shore-based fishery.

With the simultaneous growth of both the fishery and the local shark population, I saw an opportunity to develop research that would allow me to combine my passions with my profession—the ocean, fishing, and science—in a place that’s deeply meaningful to me, where I’ve lived and personally witnessed ecological change over the course of my life. These observations made me wonder what was really going on with sandbar sharks in our local waters. I was curious to know more about their demographics in the region—essentially the who, what, when, where, and why—including which sexes and age groups are present, how much time sharks spend here, whether the same individuals return annually, whether individuals or groups of individuals use certain locations extensively, what environmental conditions bring the species here (habitat use), and what behaviors the sharks display when calling Nantucket Sound home.

The Research

In order to collect scientific data, I rely on two main techniques: fishing and tagging sharks with two types of electronic tags: acoustic tags and accelerometers.

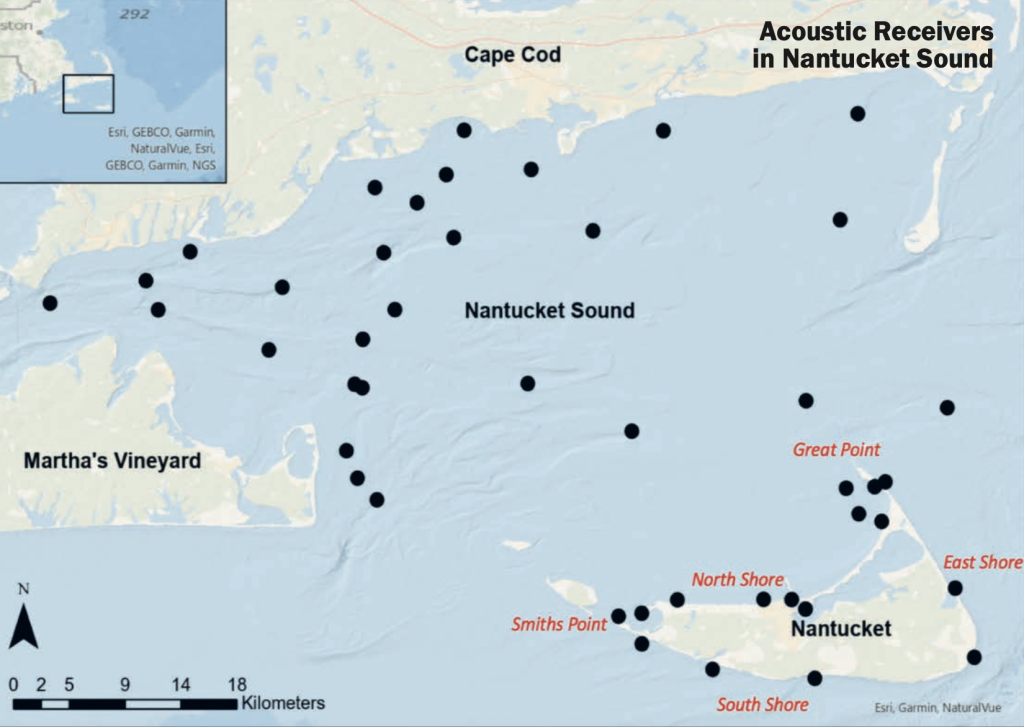

Acoustic tags allow me to identify the areas sharks are using, track their movements between locations, monitor residency, and document annual migrations and returns to the region. Acoustic telemetry functions like EZ-Pass—tags are programmed to emit a unique high-frequency signal (inaudible to humans and sharks) every couple of minutes over a period of up to 7 years. Whenever a tagged shark swims near the underwater receivers deployed around Nantucket and in Nantucket Sound by the New England Aquarium, its presence is recorded. We’re also able to collect information from acoustic tags should the sharks move out of our study area and be detected by other researchers’ receivers, thanks to coordinated efforts of acoustic telemetry data sharing networks.

Accelerometers track motion, helping me understand the fine-scale swimming behavior of sandbar sharks. Specifically, accelerometers measure movement across three axes—up/down, side-to-side, and forward/backward—the same data your phone uses to track steps—along with water temperature and depth. We embed the accelerometers in an orange float package that also includes a VHF and satellite tag to help us recover the package once it detaches from the shark. Some of our float packages are also equipped with cameras that provide video footage from the shark’s point of view, allowing us to create a comprehensive behavioral profile. We attach the float package to the dorsal fin with a galvanic link that dissolves after a few days and lets the package float to the surface. We then can track the package’s satellite signal to within a mile or so and use the VHF tag to pinpoint and recover it. Sometimes, packages can remain at the surface for hours or days, drifting with the current before we’re able to retrieve them. It’s like finding a needle in a haystack…but at least this needle is sending out multiple signals!

My recovery missions have included everything from fruitless offshore searches to successful beach walks with my dog—and once, even to someone’s driveway. After I recover the package, I download the data from the accelerometer and redeploy the package on another shark.

But in order to deploy tags, we first must catch sandbar sharks. Tagging days typically involve early mornings, bait runs, and tightly organized plans. Usually, it’s me, a volunteer or two, and local charter captain Diogo Godoi of Gorilla Tactics Sportfishing, with whom I’ve been working for the past three years.

Bluefish make excellent bait, so we typically start by trying to catch a few. On good days, catching bait is quick; on a slow day, it takes hours. Some of the best mornings involve seeing hundreds of bluefish tailing at the surface a couple miles offshore—quiet, sleek, and smelly. Doubling up on bait is always a great way to start the day.

Believe it or not, sandbar sharks can sometimes be finicky and difficult to catch. Sometimes, we wait a while; sometimes, we never get a bite. I’ve seen the sharks circle the bait, nose it, and swim away without ever taking a bite. Sometimes, they circle the area for a long time before finally attempting to take the bait. Other times, they grab it, swim off, and drop it just moments later. Then, there are the other moments when they strike with zero hesitation, the line suddenly tearing off the reel. On good days, the action starts quickly.

While sandbar sharks put up a powerful fight that can quickly exhaust a novice angler, they aren’t thoroughbreds. They typically make a few intense, dramatic runs, and after that, they are usually at the boat, but getting them close is only half the battle.

Securing a shark boatside takes some effort, and often a good dose of salt, sweat, and a bit of exasperation. Once the shark is secured, I identify its sex, measure the length, and insert an external identification tag from the NOAA Cooperative Shark Tagging Program. If the shark is recaptured in the future, it can be identified by the unique ID number on the tag.

Next, I carefully roll the shark into tonic immobility—a sleep-like state—and perform minor surgery to implant the acoustic tag into its body cavity. During this procedure, we use a numbing agent to minimize discomfort and ensure proper animal welfare. To deploy the accelerometer tag, I return the shark to the upright position and attach the float package to the side of its dorsal fin. Not every shark we catch receives an accelerometer tag package, but those that do also get an internal acoustic tag, allowing me to relate their movements to their location.

After the tags are secured, we remove the hook—crimped barbs help speed removal and reduce tissue damage—and release the shark. This moment is one of my favorites: watching the shark swim off, knowing it is contributing data to our understanding of this species around my home island. And, who knows? It might even be caught again in the future.

The Results

To date, I’ve caught and released over 200 sandbar sharks for this project, tagging 75 of them with an acoustic tag. My data suggest that the local sandbar sharks’ population is composed primarily of larger juveniles and adults, and more females than males. Many individuals exhibit consistent, annual use of Nantucket Sound, with 60 returning for at least two years, several for three years, and some for four years. Acoustic tag data also show that juveniles use both Cape Cod and Nantucket waters extensively, while adults seem to favor Nantucket. The local population’s seasonal migrations appear to be triggered by water temperature and day length, with most traveling to the Carolinas in the winter.

Recapture events also provide additional data. In 2023, one of the sharks I tagged was recaptured just two days later in the same area by a local fisherman I’ve worked with before. Last August, my friend recaptured the very first shark that Captain Diogo and I had tagged back in 2022, only two miles from the original tagging site. Just a few days later, another shark I tagged in 2023 was recaptured by a different local fisherman on exactly the same day I tagged it—only a mile from its original location.

Together, our acoustic tag and recapture data reveal a strong seasonal and annual presence of large juvenile and adult sandbar sharks in Nantucket Sound, typically from mid-June through early October. The consistent, year-to-year use of the same locations in Nantucket Sound—what we fish nerds call “site fidelity”—suggests that our local waters not only meet the ecological needs of sandbar sharks but also provide favorable conditions.

Individuals remain in the vicinity of Nantucket anywhere from a single day to more than 60 days, with most staying for more than two weeks. Most use the Great Point area for extended hours or days at a time. Their swimming behavior suggests a “yo-yo” pattern—moving between shallow and deeper areas around Great Point. Because sharks sink if they stop swimming, this descent-glide pattern likely helps conserve energy. We’ve also seen signs of aggregation behavior around Great Point. Video footage from camera-equipped tags has captured as many as six sharks in a single frame—offering a rare, valuable glimpse into their social dynamics. Sharks aggregate for various reasons, including reproduction, foraging, predator avoidance, preferred habitat, thermal preferences, and more. While I am not certain of the exact reason our local sandbar sharks seem to aggregate, my data hints that it may be related to a combination of factors including preferred environmental conditions and favorable habitat that may support optimal energy use.

The Importance

My data addresses a longstanding knowledge gap about the distribution and behavior of sandbar sharks around Nantucket and builds on Greg Skomal’s seminal work on the demographics of these sharks in Nantucket Sound. My data suggests that the current average size of sandbar sharks in our area is approximately 9 inches larger than the sizes reported by Skomal from 1989 to 2002 in the Martha’s Vineyard region. While the difference in average size may seem modest, the smaller sizes reported in Skomal’s data could reflect regional differences in sampling locations (I have not yet sampled around Martha’s Vineyard) or demographic shifts driven by intense fishery pressure. Skomal’s data was collected during the peak of overfishing for sandbar sharks, a period when larger individuals were likely consistently removed from the population, thereby reducing the average size. This emerging time series provides valuable context for future assessments and may help identify shifts in local population structure, how the population is responding to pressures such as fishing, habitat alteration, and environmental change, and the evolving use of Nantucket Sound by sandbar sharks.

In addition to informing local species-specific trends, a clearer understanding of sandbar shark presence and movement patterns can also reflect broader ecosystem changes in the Nantucket Sound area. For instance, if ocean temperatures in the waters in Nantucket Sound rise over the next five to 10 years, we may see sandbar sharks arriving earlier, staying longer, or even extending their range further north. These shifts in the duration of sandbar sharks’ presence, absence, or residency can serve as indicators of local ecosystem change, positioning these sharks as valuable bioindicators of the health and stability of our local marine environment.

The repeated presence of sandbar sharks in Nantucket Sound also emphasizes the importance of our local waters to this species. An Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) is defined as waters, marine or fresh, necessary for fish to spawn, breed, feed, or grow to maturity, and are critical areas that support the long-term health of fish populations. Currently, most of Nantucket Sound and the surrounding waters are not designated as an EFH for sandbar sharks. While my data does not show that sandbar sharks are reproducing or breeding here, their extended presence in this area suggests that our waters may support important biological activities such as foraging and growth. Although the process of updating EFH designations is complex, these findings point to the potential ecological value of Nantucket Sound for sandbar sharks and may help guide future species and resource management considerations.

Additionally, identifying aggregation sites highlights areas vulnerable to threats like fishing pressure and habitat degradation. Even in catch-and-release fisheries, repeated disturbance in aggregation spots can increase stress, injury, and mortality across many individuals simultaneously. While I have not determined the main drivers of the sandbar shark aggregations around Great Point, documenting their presence—especially when paired with our other research on post-release mortality—can help assess the extent of impact the local fishery may have on this aggregation.

As we continue to learn more about the role the Nantucket Sound area plays in the lives of sandbar sharks, it’s equally important for those who encounter them to do their part in supporting responsible shark fishing. Regardless of how frequently you fish for sandbar sharks, be sure to check the latest Massachusetts regulations, use a circle hook, minimize handling time, and have a plan in place for the safe handling and release of each shark.

Lastly, my research also has the potential to benefit the broader Atlantic sandbar shark population. When integrated with other ongoing studies, our findings on demographics, site fidelity, and seasonal return rates can help refine population models, ultimately supporting more effective conservation and fisheries management decisions for sandbar sharks in U.S. Atlantic waters.

Stay tuned, as I’ve only skimmed the surface and there’s still so much to discover.

If you’d like to learn more about this work, the science behind the tags, and other ongoing research at the New England Aquarium, visit neaq.org.

Related Content